In the paintings of ancient female painters, women step out of their role as victims, transcend the hierarchies imposed on them and take revenge on the patriarchy, at least in the imagination. A 17th-century "Kill Bill?" Quite possibly.

This text has been auto-translated from Polish.

The library in our district has had a feminist section for several years. Literature written by women, essays, accessibly written sociology, history and cultural studies. Also books for children, for example, a superbly illustrated book on gender differences, one of a series that also includes an explanation of class differences and mechanisms of discrimination.

Next to it is a collection of biographies of more and less famous women who have made history. It begins with female painters from prehistoric caves and has a great title: Don't Tell Us Fairy Tales. It's better than Sleeping Beauty, my daughter loved listening to these stories before falling asleep.

Unfortunately, I am not writing about Poland. If such libraries exist somewhere in Poland, I haven't come across them. This is about my neighborhood in Madrid, where I spent a good chunk of my life.

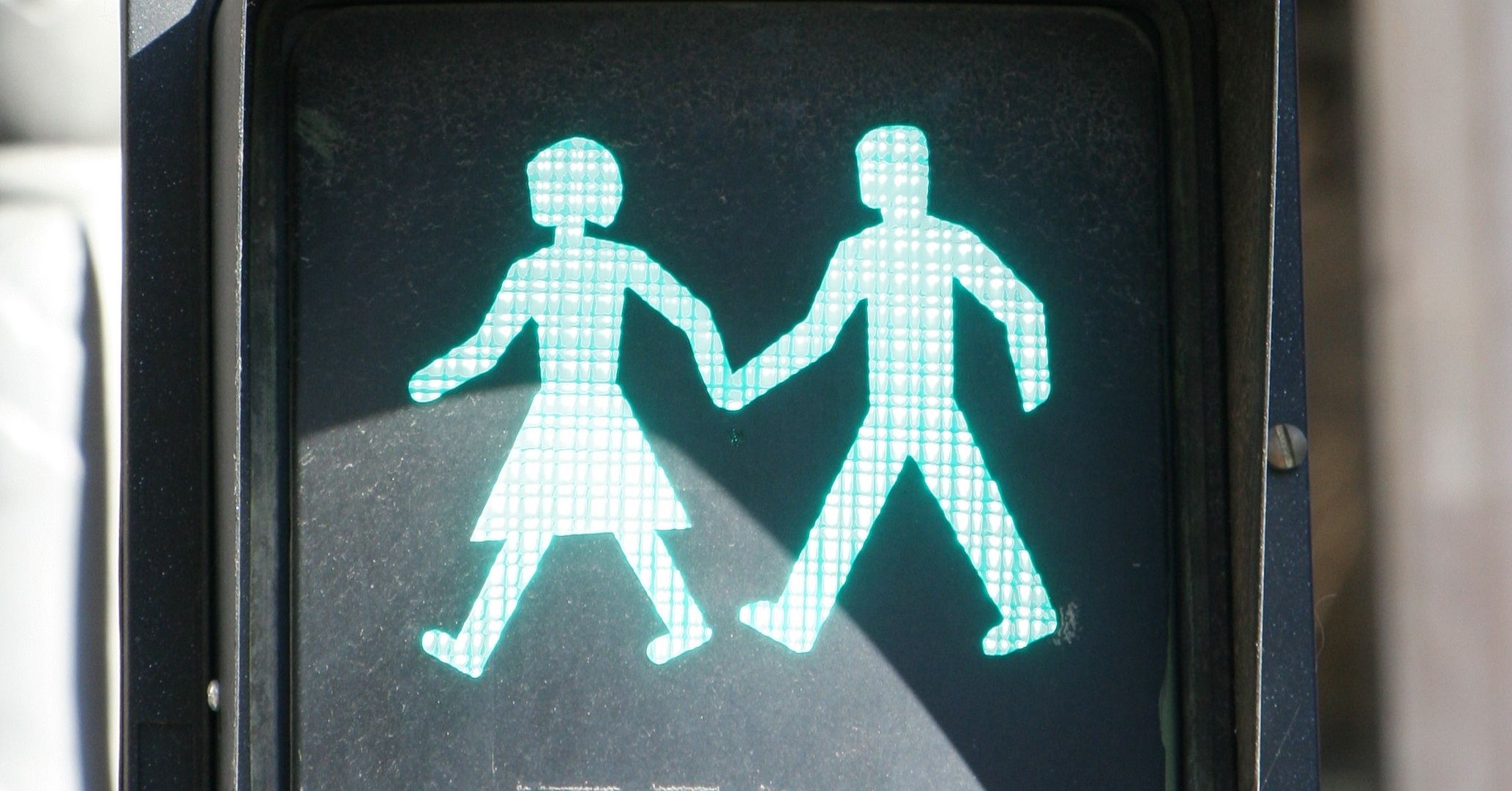

Working on equality is not easy and there is still a lot of work to be done, but Spain seems to me a good example of which way to go. The differences may be small, but they add up to a different, freer environment. At pedestrian crossings, the lights depict a girl or a couple - single-sex or mixed - marching briskly. A guy, of course, is also met. Green light - so forward.

Gabriele Münter

The bottom line in Madrid is that the feminist section in the library is not a corner for women that has been graciously made available so that everything can stay as it was. We're not dealing with a niche for freaks, rather a change embracing the whole.

I feel this in my field, which is culture. I go to exhibitions in Spain, whose offerings look really impressive. I like the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum the most, especially the temporary exhibitions, always well prepared. This time I ended up at Gabriele Münter. I am not an art historian, rather an amateur who likes to look and read. I had heard of Münter, but she was always somewhere on the margins. In albums about German Expressionism one illustration. More often photos of Der Blaue Reiter group or Wassily Kandinsky taken by her. More often a painting by Kandinsky depicting Münter at the easel than what she herself painted.

Münter was a woman unique for her time. She was born in Berlin, but her parents met and married in the United States. After her father's death as a 20-year-old girl, she went with her sister to Missouri, Arkansas and Texas for two years. Later, in 1904-1907, she already traveled with Kandinsky in Europe, Italy and southern France. She also visited Tunis. Able to defend her independence, she photographed and painted.

As a woman, she was not allowed to enter art academies, so she began her studies at the Damen Akademie in Munich, run by the Association of Women Artists. She then joined the Phalanx School, where she studied painting with Kandinsky. Together they discovered Murnau and soon lived together - on a cat's paw - in the house Münter bought. It was there with Marianne von Verefkin, Jawlensky and Kandinsky that they experimented in the mountainous open air, giving rise to German Expressionism.

Four artists - two couples, of whom only the men have gone down in art history. Von Verefkin quickly stopped painting so as not to compete with Jawlenski. Münter entered the Der Blaue Reiter group, but she was not treated as an equal among equals. She was not a painter to her colleagues, but merely a "woman who paints."

An exhibition at the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum restores her rightful place. One can see and compare works. It looks like they inspired each other and made such culturally important discoveries together. The paintings show the interior of the house, the daily life that went by painting, talking and working in the garden, but also the collection of folk art: Bavarian sculptures and paintings on glass. I was familiar with Kandinsky's works in this technique and associated them only with him. It turns out that they discovered it and experimented together.

It is also important that the house where all this was happening was owned by Gabriele Münter. She was the one who had the idea for this way of life and not another. It was she who gave it a material basis.

The heroines

Münter's exhibition creates a new canon. Walking out of it, I have in my mind not only Kandinsky, Jawlensky and Franz Marc. They are already together with Münter and von Verefkin. I will also remember Franz Marc's aggressive attacks, calling Münter "a flea taking a journey together with the Blue Rider." I watched and know that she is no flea.

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum has had this kind of policy for years. It's a conscious choice, because the permanent exhibition has also changed. The gallery of 20th century paintings featured artists who were not there before. It's not about parity, rather a return to reality after decades of patriarchal bias. The curators felt that this was a part of art history that could not be overlooked.

Temporary exhibitions such as Heroinas (Heroinas; an exhibition organized by the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and Fundasion Caja Madrid in 2011) and the recent Mistresses (Maestras; opened in the fall of 2023), which featured paintings by Artemisia Gentileschi, Angelika Kaufmann, Clara Peeters, Rosa Bonheur, Mary Cassat, Berthe Morisot, Mari Blanchard, Natalia Goncharova or Sonia Delaunay.

In addition, there are solo exhibitions. In the past few years I have seen Georgia O'Keeffe and Artemisia Gentileschi at Thyssen-Bornemisza. The latter exhibition in particular was particularly moving. Gentileschi did not have it easy. She lived three hundred years before Münter, and the whole world at the time was against her. She studied in the workshop of her father, the painter Orazio Gentileschi, who entrusted her to Agostino Tassi, a master of perspective and trompe-l'œil. The teacher turned out to be a rapist. Gentileschi was eighteen years old at the time.

On the surface, she appears to be a painter similar to other Baroque painters: biblical scenes and saints. However, when we look at the choice of subjects, the matter turns out to be more interesting. There are a lot of women. Notable are the paintings depicting Susanna and old men in several realizations. The difference with male depictions of the same subjects is striking. It is difficult to stand next to the old men and join the group of voyeurs. Underneath the convention that has naturalized male usurpation and power, violence begins to become apparent. For Gentileschi, the subject is sexual violence and the situation of the victims. It has to be seen to understand what an important change this is.

Among the protagonists of this painting are also women who resort to violence themselves. Judith returns several times, as well as Jael, who kills the Canaanite chief Sisera by piercing his temple with a tent peg. Knowing Gentileschi's story, it is hard to resist the temptation not to look for additional meanings in these scenes. To step out of the role of victim, to transgress imposed hierarchies, but also to retaliate against the patriarchy, at least in the imagination. A seventeenth-century Kill Bill? I don't know how it worked in Artemisia Gentileschi's time, but today, in the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum, this painter is certainly a causal force. Her voice has become audible. I walk out onto the Paseo del Prado with a new perspective on Italian seicenta art and, more broadly, on the world in which I live.

Tyssen-Bornemisza is not the only one working this way. At Fundación Mapfre, a small but very interesting exhibition dedicated to an event from more than 80 years ago was on display until January 5. In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim organized one of the first exhibitions devoted entirely to the work of women in her New York gallery. It featured the works of 31 female artists. One would like to mention them all by name. What emerges is a not-so-masculine history of Surrealism - with such forgotten stars as Leonor Fini or Maret Oppenheim. It's hard to say why the latter is better known as a Man Ray model than as an artist in her own right.

Historical, not hysterical

In 2022, I participated in the Madrid Manifesto. It was difficult to get to it, because the buses came to a stop near our house full of people and didn't even stop. I had the impression that the whole city was pouring into the center. And that was indeed the case. The streets leading towards Atocha Station were blocked, the bus dropped us off early and we walked along with a rather colorful crowd to get just to the southern end of the demonstration. Meeting friends coming from another direction was out of the question. The gathering stretched all the way to Cibeles, some two kilometers to the north.

We walked with Mirka - my daughter - between people and talked. We met two girls there who were memorable to me. They were holding banners. On the first one was the inscription: "No somos hystericas, somos historicas," meaning "We are not hysterical, we are historical." Historic in a double sense: not only as full participants in history past and present, but also as those who are just making a revolution. A long one, conducted systematically and hopefully - effective. The second banner read: "Lo contrario del feminismo es ignorancia," or "The opposite of feminism is ignorance."

Nothing to add, nothing to take away. Spaniards are fortunate that these girls' slogans have become obvious to almost everyone. They are also being carried out by institutions such as Thyssen-Bornemisza and Fundación Mapfre, and no one is surprised. Trump won't stop it either.