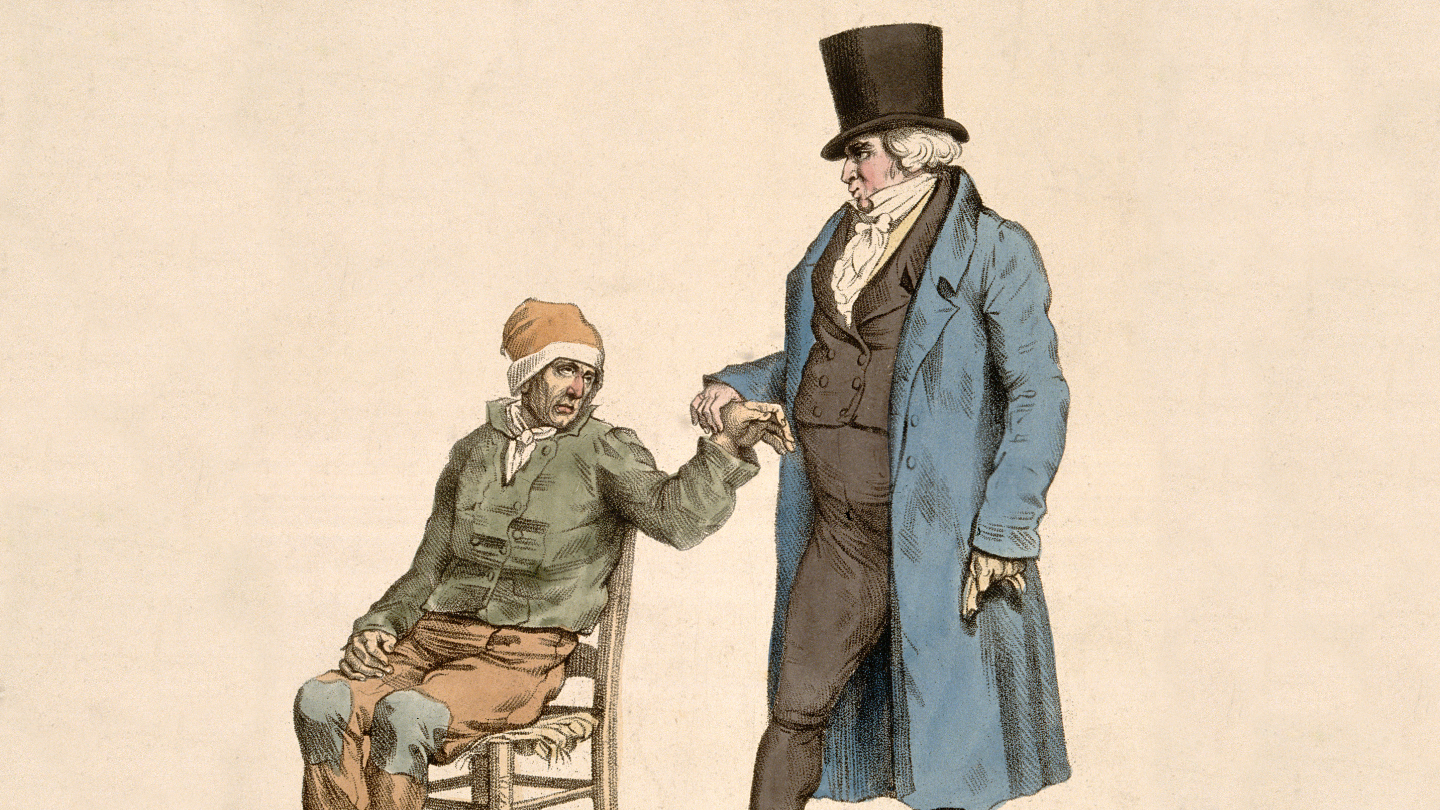

Kilka dni temu na portalu X miała miejsce ożywiona dyskusja na temat zarobków lekarzy, w których ci ostatni oczywiście wzięli udział – bo lekarze nie lubią, gdy zbyt szczegółowo analizuje się ich zarobki.

Argumenty medyków były mało oryginalne i głównie skupiały się na ogromnym wysiłku, który włożyli w edukację, dodając do czasu kształcenia zawodowego nawet okres liceum, żeby efektowniej wyglądało. W toku dyskusji jeden z lekarzy się jednak wysypał i zapytany o to, dlaczego w ogóle wybrał ten zawód, bez ogródek stwierdził: „moja rodzina zawsze była lekarska”.

W tym przypadku można mu wierzyć na słowo, gdyż dziedziczenie zawodu w tej branży to raczej norma. Człowiek od małego wysłuchuje rozmów rodziców w domu na temat dnia pracy, więc potem łatwiej przyswaja wiedzę z tej akurat dziedziny. Jest to dla niego tak naturalne, że potem nawet o tym nie pamięta – w głowie zostały mu tylko lata nauki i ciężkiej pracy, których używa jako argument w dyskusjach na X.

Gdyby ten mechanizm odnosił się tylko do jednego, dosyć specyficznego zawodu, to łatwiej byłoby mu przeciwdziałać. Problem w tym, że często dziedziczy się nie tylko zawód lekarza, ale w ogóle pozycję klasową i zawodową. Inaczej mówiąc, dzieci lekarzy nie biedują, nawet jeśli jakimś przypadkiem same nie zostały lekarzami.

W Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej wygrywasz już na starcie

Pokazuje to najnowsza edycja badania EBOiR Life In Transition, w którym analizowana jest sytuacja ekonomiczno-społeczna w państwach byłego bloku komunistycznego, z Niemcami włącznie, ale porównawczo pojawiają się tam również państwa ze wszystkich rejonów świata.

Najczęściej obszarem zainteresowania jest tam nierówność szans, wykazywana jako znaczenie dla późniejszych zarobków czynników, na które samemu nie ma się wpływu. Te czynniki to płeć, miejsce urodzenia (miasto czy wieś) oraz kapitał kulturowy rodziców, na który składają się ich wykształcenie, grupa zawodowa oraz liczba książek w domu.

Autorzy badania umownie podzielili państwa na cztery grupy. Do krajów, w których nierówności dochodowe są zarówno wysokie, jak i predeterminowane (wysokość zarobków w dużej mierze kształtuje się już w momencie urodzenia), należą przede wszystkim państwa Ameryki Południowej – Chile, Brazylia, Kolumbia czy Argentyna – oraz niektóre kraje Europy (Hiszpania, Rumunia, Łotwa).

Państwa, w których nierówności zarobkowe są wysokie, ale nie są determinowane już w momencie przyjścia na świat, to głównie kraje Azji Środkowej (Uzbekistan, Tadżykistan, Kirgizja), Bałkanów (Macedonia, Czarnogóra) i położone w pobliżu Kaukazu (Armenia, Azerbejdżan, Gruzja, Turcja). Jest też grono państw, w których co prawda rozwarstwienie dochodowe jest raczej niskie, ale za to nierówność szans wysoka – właśnie w tej grupie znalazła się Polska, której towarzyszyło bardzo wiele krajów Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej (Węgry, Litwa, Słowacja, Słowenia, Estonia i Bułgaria).

Istnieje jednak również grupa krajów, które nie dość, że mają niskie nierówności, to jeszcze występuje tam niska nierówność szans. W gronie tych szczęściarzy znalazły się między innymi narody nordyckie (Norwegia, Dania, Finlandia), Holandia, Niemcy, Szwajcaria i Czechy. Oczywiście także tam czynniki, na które nie ma się wpływu, w jakiejś mierze decydują o zarobkach, jednak ich skutki są bardziej ograniczone.

Ile w Polsce znaczy kapitał kulturowy

Wskaźnik nierówności szans w publikacji EBOiR jest wykazywany jako odsetek całkowitych nierówności dochodowych. Inaczej mówiąc, skoro w Holandii wynosi on niespełna 20 proc., to jedna piąta tamtejszych nierówności dochodowych jest efektem czynników określanych w momencie urodzenia – czyli płci, miejsca zamieszkania oraz kapitału kulturowego rodziców.

Holandia okazała się jednym z prymusów, jednak i tak nie ma startu do Danii, w której nierówność szans wynosi ledwie 5 proc. W Niemczech jedna czwarta rozwarstwienia dochodowego to efekt nierówno rozłożonych szans, a w Czechach jedna trzecia. Na drugim końcu zestawienia znalazły się Brazylia i Azerbejdżan, gdzie prawie 60 proc. nierówności dochodowych to efekt czynników wynikających z samego urodzenia.

Pod tym względem Polska wypadła jako jeden z krajów najmniej rozwarstwionych pod względem dochodów, jednak z ogromnym wpływem czynników, na które samemu nie ma się wpływu. Wskaźnik nierówności szans wyniósł 50 proc., czyli połowa rozwarstwienia dochodowego wynika właśnie z tych pierwszych. Nierówność szans jest więc w Polsce dziesięć razy większa niż w Danii i 2,5 razy większa niż w Holandii.

Podobny wynik do Polski zanotowały między innymi Węgry, Serbia, Czarnogóra i Chile. Poza Brazylią nieco większa niż w Polsce nierówność szans występuje w Bułgarii, Rumunii, Litwie, Azerbejdżanie i Peru – przy czym we wszystkich tych państwach występują też znacznie większe nierówności ekonomiczne, nie można więc powiedzieć, że ogółem nasza sytuacja jest podobna. Niewątpliwie jest dużo lepsza. Wpływ specyfiki domu rodzinnego na sukces zawodowy jest tam porównywalny, ale osiągnięcie sukcesu nie daje w Polsce tak dużej przewagi ekonomicznej jak w wymienionych wyżej państwach.

Co gorsza, nierówność szans w Polsce – jak i we wszystkich analizowanych państwach łącznie – szybko rośnie. W poprzednim badaniu (2016) czynniki wynikające z urodzenia wpływały na jedną trzecią rozwarstwienia dochodowego nad Wisłą – obecnie już na połowę.

Polska wyróżnia się też pod względem wpływu kapitału kulturowego rodziców na nierówności. Kapitał kulturowy rodziny odpowiada tu aż za 77 proc. nierówności szans, miejsce dorastania za 18 proc., a płeć ledwie za 5 proc. Inaczej mówiąc, dziewczynka mająca dobrze wykształconych rodziców będzie mieć w Polsce zdecydowanie łatwiej niż chłopiec z domu, w którym oboje partnerzy mają wykształcenie zawodowe.

Dlaczego walka z nierównościami jest w interesie ludzi sukcesu

Oczywiście kapitał kulturowy rodziny, a w szczególności wykształcenie, odgrywają ogromną rolę w karierze zawodowej ich potomstwa pod każdą szerokością geograficzną.

Przykładowo Paul Novosad, ekonomista z należącej do Ivy League uczelni Dartmouth, wspólnie ze współpracownikami zbadali wykształcenie, zawód i szacowane dochody ojców wszystkich laureatów Nagrody Nobla w latach 1901–2023. Ojcowie połowy noblistów należeli w swoim kraju do 5 proc. najzamożniejszych. Aż dwie trzecie noblistów to potomkowie mężczyzn należących do górnych 10 proc. pod względem zarobków. Z najbiedniejszych 10 procent nie wywodzi się żaden dotychczasowy laureat Nobla, za to ojcowie trzech czwartych noblistów należeli do 10 proc. najlepiej wykształconych.

Wpływ pochodzenia na efekty wysiłków zawodowych jest więc oczywisty i wysoki. Na miejscu rodziców tych wszystkich przemądrzalców z X-a, którzy mogą godzinami wypisywać peany na cześć swojej ciężkiej pracy, bardzo bym się wkurzył. Zapomnieliście o mamie i tacie?

Tak naprawdę w interesie tzw. ludzi sukcesu jest walka z nierównością szans, a nie zaprzeczanie jej. Gdy nierówności są niskie, rośnie szacunek do osób o wysokim statusie, bo z góry zakłada się, że ich pozycja to przede wszystkim efekt osobistych zasług. Za to gdy nierówność szans jest wysoka, szacunek i zaufanie do prestiżowych zawodów spada, gdyż z definicji uważa się ich za dziedziców statusu, nawet jeśli niektórzy na takie określenie nie zasłużyli. Nie mówiąc już o takiej drobnostce, że akurat w odniesieniu do lekarzy jest to szczególnie istotne, gdyż brak zaufania społecznego do tego zawodu skutkuje różnymi bardzo szkodliwymi zjawiskami – na przykład unikaniem szczepienia dzieci albo lekceważeniem przepisów pandemicznych.

Wspieraj

Wspieraj

Wspieraj

Wspieraj  Wydawnictwo

Wydawnictwo

Zaloguj się

Zaloguj się