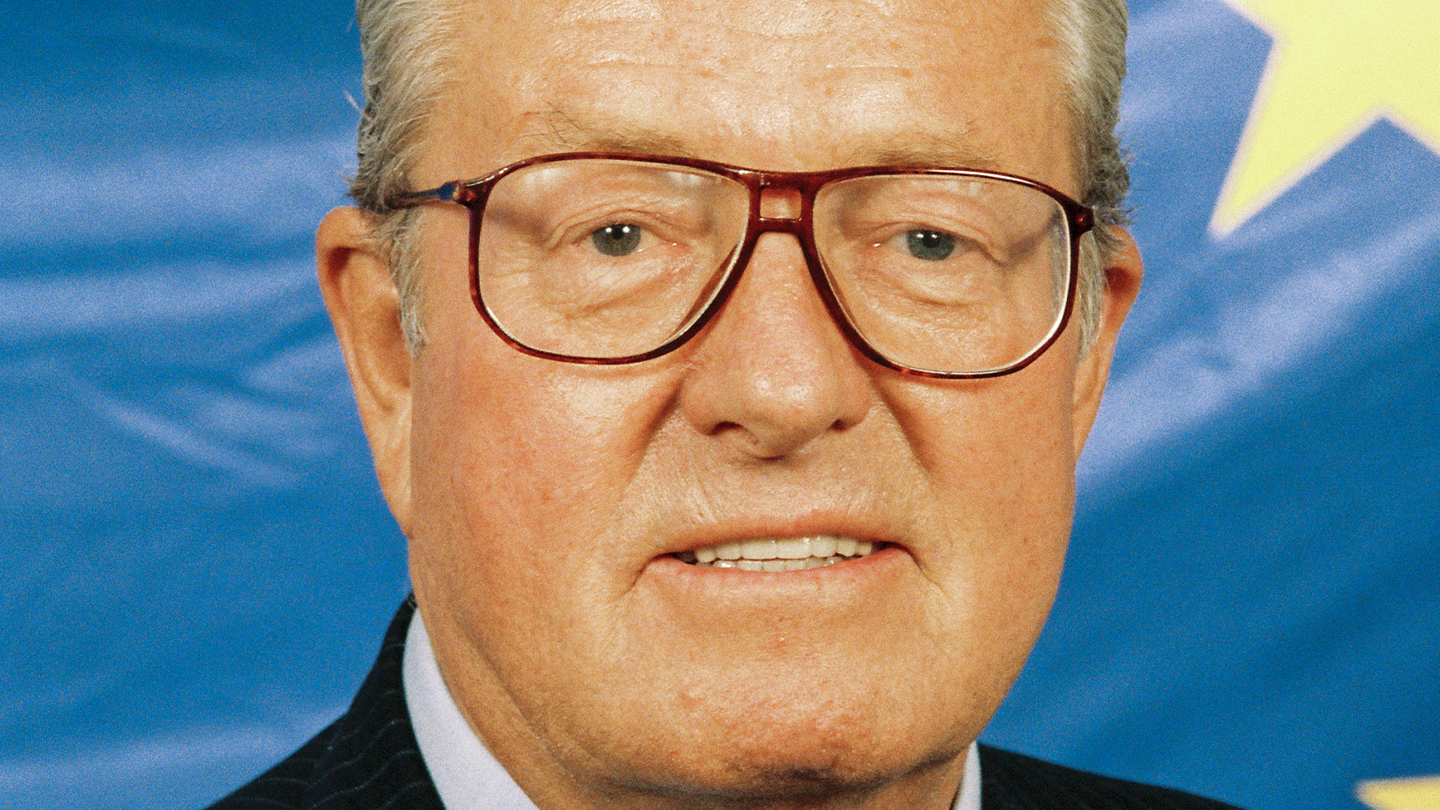

Według starego porzekadła o zmarłych wypada mówić dobrze lub wcale. Gdyby się go trzymać, to nekrolog Jeana-Marie Le Pena musiałby być pusty, przynajmniej w dziale dotyczącym jego aktywności publicznej. Kariera polityczna twórcy Frontu Narodowego została bowiem zbudowana na sianiu nienawiści, negowaniu lub umniejszaniu Holocaustu, czynieniu z muzułmanów kozłów ofiarnych i nieprzerwanych bataliach sądowych, gdzie Le Pen zwykle występował w charakterze oskarżonego.

Jak na ironię, patriarcha francuskiej skrajnej prawicy odszedł akurat w dziesiątą rocznicę zamachu na „Charlie Hebdo”, z którym zawsze był skłócony. Satyryczne pismo swego czasu walczyło o delegalizację Frontu Narodowego, mając ku temu bardzo słuszne powody, zwłaszcza jeśli popatrzeć na korzenie głównej nacjonalistycznej partii Francji oraz jej współzałożycieli.

Nazistowscy koledzy Le Pena

Gdy w 1972 roku powstał Front Narodowy, na jego lidera wybrano Jeana-Marie Le Pena, który miał już za sobą krótkie doświadczenie parlamentarne, trafiając do Zgromadzenia Narodowego z list populistycznego ruchu Pierre’a Poujade’a. Był to wybór w dużej mierze taktyczny, Le Pen należał bowiem do najbardziej umiarkowanych wśród założycieli nowej partii. Kim więc byli pozostali?

Znajdziemy wśród nich chociażby członków terrorystycznej Organizacji Tajnej Armii (OAS), która sprzeciwiała się demontażowi francuskiego imperium kolonialnego i odpowiadała za nieudane zamachy na prezydenta De Gaulle’a. Do tego dojdą kolaboranci z okresu II wojny światowej, zaangażowani w budowę Francji Vichy, należący do faszystowskich bojówek i odpowiedzialni za brutalne represje wobec ruchu oporu. Jakby tego było mało, współzałożycielami Frontu Narodowego byli esesmani z francuskiej dywizji Waffen SS, tacy jak Léon Gaultier czy Pierre Bousquet.

Ten ostatni, pełniący funkcję skarbnika nowej partii, kilka lat wcześniej został wyrzucony z rasistowsko-nacjonalistycznego Europejskiego Ruchu Wolności za nazizm i organizowanie seminariów poświęconych czytaniu Mein Kampf Adolfa Hitlera. Z kolei tuż po wojnie Bousquet miał trafić na gilotynę za kolaborację, jednak karę śmierci zamieniono ostatecznie na kilka lat pozbawienia wolności. Wielu innych z wczesnych liderów FN również miało za sobą niewykonane wyroki śmierci, pobyty w więzieniu lub karę degradacji narodowej (specjalna sankcja odbierająca kolaborantom część praw obywatelskich), ale Le Penowi nie przeszkadzało zostanie twarzą organizacji z takimi kadrami.

Sam Jean-Marie nie był od nich daleki poglądami. Także wybielał kolaborancką Francję Vichy, nazywał marszałka Pétaina bohaterem większym od De Gaulle’a, a opuszczenie Algierii uważał za czyn hańbiący tego ostatniego. Zresztą kilkanaście lat przed założeniem Frontu Narodowego Le Pen zgłosił się ochotniczo do walki o utrzymanie francuskiego panowania nad północnoafrykańskim państwem, co stanowi kolejną niechlubną kartę jego biografii.

Od torturowania Algierczyków do drugiej tury wyborów prezydenckich

We francuskiej Algierii Jean-Marie Le Pen pełnił funkcję oficera wywiadu i zasłynął brutalnością, z jaką traktował podejrzanych o współpracę z narodowowyzwoleńczym FLN-em, a czasem i przypadkowe osoby. Liczne relacje – zarówno ofiar, jak i towarzyszy broni – mówią o katowaniu Algierczyków, torturach z użyciem elektrowstrząsów i egzekucji niektórych z nich. W domu jednej z ofiar przesłuchania (torturowanej i zabitej na oczach dzieci) francuski porucznik zgubił swój nóż, podejrzanie podobny do modelu oryginalnie wytwarzanego z myślą o Hitlerjugend, z wygrawerowanym napisem „J.M. Le Pen 1er REP”.

Sam zainteresowany kilka lat po wojnie przyznał się do stosowania tortur w Algierii, ale tłumaczył to koniecznością uzyskania kluczowych informacji od „terrorystów” i zaprzeczał większości oskarżeń. Czasem pozywał media i historyków wypominających mu torturowanie cywilów, chociaż częściej meldował się w sądach jako oskarżony. Kariera polityczna Le Pena upłynęła bowiem pod znakiem kontrowersji, zaciekłych polemik i mowy nienawiści.

Za apologię zbrodni wojennych, dyskryminację osób LGBT, ataki na mniejszości religijne i obelgi pod adresem przeciwników politycznych założyciel Frontu Narodowego usłyszał łącznie ponad 25 wyroków skazujących. Kilka z nich dotyczyło stwierdzeń Le Pena, że komory gazowe były jedynie „detalem historii” – stąd po jego śmierci często ironizowano, że Jean-Marie stał się tymże detalem. Inne procesy sądowe dotyczyły jego rasistowskiej wizji Francji, w której nie widział miejsca dla obywateli niewłaściwego pochodzenia czy wyznania. Lider FN dzielił społeczeństwo na Francuzów prawdziwych i „papierowych”, wzmagając napięcia społeczne.

Mimo nieustannych batalii sądowych Front Narodowy rósł w siłę, a Jean-Marie Le Pen stał się jego niekwestionowanym przywódcą. Opierając swoje kampanie na sprzeciwie wobec imigracji, eurosceptycyzmie, radykalnym antykomunizmie i ultrakonserwatyzmie skrajna prawica zadomowiła się w latach 80. na francuskiej scenie politycznej, zdobywając w każdych kolejnych wyborach od dziesięciu do kilkunastu procent głosów. W 2002 roku dzięki rozdrobnieniu lewicy okazało się to wystarczające do zaprezentowania się w drugiej turze wyborów prezydenckich, co stanowiło dla ówczesnej Francji głęboki szok, mobilizujący obywateli do masowego głosowania na Chiraca, przeciwko Le Penowi.

Jean-Marie Le Pen nie był w stanie przebić szklanego sufitu, pozostawał postacią zbyt kontrowersyjną i radykalną, za to jego córka dokonała skutecznego oddemonizowania Frontu Narodowego, zdobywając w ostatnich wyborach aż jedną trzecią głosów i czyniąc centroprawicowy rząd zależnym od poparcia nacjonalistów. Starszy Le Pen przypłacił ten proces wydaleniem z partii, ale i tak sam doczekał się daleko idącej rehabilitacji, co pokazały reakcje po śmierci nestora skrajnej prawicy.

Śmierć fetowana na ulicach, witana z żalem w kręgach rządowych

Naturalnie odejście Jeana-Marie ze smutkiem przyjęło jego środowisko polityczne, opłakując śmierć „męża stanu” i „patrioty”. Natomiast lewica nie szczędziła zmarłemu krytyki, wypominając mu wszystkie przewiny i trzeźwo stwierdzając, że umarł człowiek, ale nie jego idee polityczne, z którymi nadal trzeba walczyć. Mniej wyważone opinie miało wielu Francuzów spontanicznie świętujących śmierć Le Pena na ulicach wszystkich dużych miast Francji, gdzie odpalano fajerwerki i otwierano butelki szampana, niczym w Nowy Rok.

To z kolei spotkało się z ostrym potępieniem ze strony polityków z kręgów rządowych, z konserwatywnym szefem MSW Bruno Retailleau na czele. Postawa centroprawicy jest tu najbardziej symptomatyczna dla normalizacji radykalnej prawicy we francuskim mainstreamie. Nowy szef rządu François Bayrou śmierć założyciela Frontu Narodowego skomentował bardzo ugodowo, nazywając Le Pena ważną figurą życia politycznego Francji i wojownikiem, ale pomijając milczeniem rasizm, niechlubną przeszłość czy dziesiątki ciążących na nim wyroków sądowych. Zresztą większość macronistów wybrała milczenie całkowite, prawdopodobnie nie chcąc wyrażać swojej prawdziwej opinii o założycielu partii, z którą znaleźli się w nieformalnej koalicji.

Francja zmieniła się od 2002 roku, gdy prezydent Chirac odmówił debaty z liderem skrajnej prawicy, a sprzeciw wobec Le Pena połączył ponad 80 proc. wyborców. To były też czasy, gdy polityczne centrum wciąż należało do głównych przeciwników nacjonalistów, pamiętając o szkodliwości ich idei i korzeniach Frontu Narodowego. Swego czasu, gdy Le Pen wraz z kolegami przyszedł zakłócić spotkanie Simone Veil, twarzy walki o prawa kobiet i zarazem Żydówki ocalałej z Holocaustu, ta rzuciła w ich kierunku „nie boję się was, przetrwałam spotkanie z gorszymi niż wy, jesteście jedynie esesmanami w krótkich spodenkach”.

Teraz ich spadkobiercy są o krok od władzy, usilnie starając się na nowo przepisać niewygodną przeszłość. Dlatego warto przypominać o prawdziwych poglądach Jeana-Marie Le Pena czy tożsamości innych założycieli Frontu Narodowego, bo chociaż nacjonaliści wiele zrobili dla poprawienia wizerunku, to niedaleko pada jabłko od jabłoni.

Wspieraj

Wspieraj

Wspieraj

Wspieraj  Wydawnictwo

Wydawnictwo

Zaloguj się

Zaloguj się