W 2018 roku hiszpańska Grupa CAF przejęła za 300 mln euro jedną z pereł polskiego przemysłu, producenta pojazdów komunikacji zbiorowej Solaris. Niemal w tym samym czasie ogromne problemy przechodziło drugie flagowe przedsiębiorstwo znad Wisły, czyli producent pojazdów szynowych Pesa, którą przed upadłością uchroniło przejęcie przez Polski Fundusz Rozwoju. Do dziś jest on właścicielem bydgoskiego przedsiębiorstwa. Pesa jest więc obecnie de facto spółką skarbu państwa.

Kilka lat później sytuacja może się odwrócić, gdyż chęć przejęcia hiszpańskiego producenta pociągów wysokich prędkości Talgo ogłosiła Pesa. Talgo próbowali już przejąć Czesi ze Škody oraz Węgrzy z Ganz-MÁVAG, którzy oferowali aż 619 mln euro. Tę ostatnią transakcję zablokowały władze Hiszpanii z powodu koligacji Węgier z Rosją. Jak pamiętamy, takim instynktem zachowawczym nie wykazał się rząd PiS, sprzedając część Lotosu węgierskiemu MOL-owi.

Pesa rozpoczęła już współpracę z Talgo, podpisując porozumienie o wspólnej produkcji pojazdów dla kolei dużych prędkości w Polsce. „Nasze memorandum z Talgo dotyczy współpracy przy budowie pociągów nie tylko dla Polski, ale zasadniczo dla krajów regionu. Myślimy więc też np. o Rail Baltice. Jesteśmy przekonani, że połączenie wiedzy i doświadczeń Pesy i Talgo, gwarantuje przedstawienie ciekawej oferty dla przewoźników obszaru Trójmorza” – stwierdził prezes Pesy Krzysztof Zdzierski w rozmowie z portalem „Rynek Kolejowy”.

Jak konkurować z gigantami z Chin i USA

Europejskie przedsiębiorstwa przemysłowe podobne fuzje przetestowały już na znacznie większą skalę. W 2019 roku powstał gigant motoryzacyjny Stellantis. Został utworzony przez dwie spółki, które same wcześniej powstały w wyniku fuzji. Mowa o koncernie Fiat-Chrysler oraz Grupie PSA, powstałej po przejęciu Citroena przez Peugeota. Według rankingu Fortune 500 obecnie Stellantis jest drugim co do wielkości producentem motoryzacji w Europie po Volkswagenie pod względem przychodów i pierwszym pod względem zysków – wyprzedzając niemiecki koncern o ponad 2 mld euro.

Oczywiście, zachwycanie się wynikami Stellantisa byłoby nie na miejscu. Koncern tnie koszty na potęgę, niedawno ogłosił zwolnienie 2,5 tys. pracowników, w tym likwidację całej fabryki w Bielsku-Białej.

Fuzja Fiata z PSA pokazuje jednak, że europejskie przedsiębiorstwa coraz częściej dochodzą do – prawdopodobnie słusznego – wniosku, że same nie są w stanie konkurować z coraz większymi gigantami z Chin i USA. A nawet z koreańskimi czebolami oraz starymi korporacjami z Japonii, takimi choćby jak Toyota, która pod względem zysków bije na głowę zarówno Stellantis, jak i Volkswagena, chociaż jej przychody są niższe od tego drugiego. Koreański Hyundai ma jedynie dwukrotnie niższe dochody od VW, chociaż jeszcze nie tak dawno samochody z tej firmy w ogóle nie były traktowane poważnie.

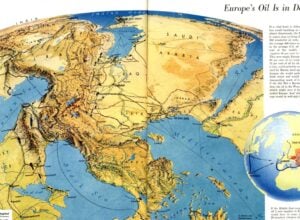

Ogólnie rzecz biorąc, Europa przegrywa z konkurentami z Azji i Ameryki z powodu wyższych kosztów. Wysokie standardy zatrudnienia czy polityka klimatyczna podnoszą znacząco wydatki ponoszone podczas produkcji, co finalnie przekłada się na niższe zyski lub wyższe ceny (a więc zwykle też niższe zyski z powodu spadku sprzedaży). Nie licząc niepoprawnych wolnorynkowców, nikt nie chciałby redukcji europejskich zdobyczy socjalnych, które tworzą nasz kontynentalny model ekonomiczno-społeczny.

To właśnie on wyróżnia Europę na tle reszty świata. Nie chodzi przecież o to, żeby wygrać rywalizację ekonomiczną z Azją, upodabniając się do niej, bo to by oznaczało de facto porażkę. Celem powinien być powrót UE do grona technologicznych i przemysłowych liderów, zachowując przy tym europejski model państwa dobrobytu.

Fuzja jako alternatywa

Alternatywnym sposobem obniżenia kosztów są właśnie fuzje. Większe przedsiębiorstwa mają znacznie szersze pole optymalizacji kosztów, gdyż mogą korzystać z efektu skali, dzięki któremu część koniecznych wydatków rozkłada się na większą liczbę wyprodukowanych jednostek.

Przedsiębiorstwa produkcyjne po połączeniu mogą też wspólnie projektować oraz kupować półprodukty. Škoda, VW i Seat mogą się bardzo różnić z zewnątrz, jednak w środku wyglądają bardzo podobnie, gdyż korzystają z dokładnie tych samych drobniejszych części. Nic dziwnego, to marki należące do tej samej grupy Volkswagen.

Zachowanie europejskiego modelu ekonomiczno-społecznego wymagać będzie niestety również bardziej asertywnej polityki handlowej. Skoro sami sobie narzucamy wysokie standardy produkcji i pracy, to równocześnie nie możemy dopuszczać do unijnego rynku producentów mających znacznie niższe, gdyż dzięki niskim cenom szybko wypchnęliby przedsiębiorstwa z kontynentu.

Do wyrównania szans służą wysokie cła oraz kierowane opodatkowanie, czyli na przykład podatek od śladu węglowego (CBAM), który UE właśnie uruchamia – zresztą stanowczo zbyt późno.

Z dużym poślizgiem UE wprowadziła także cła na samochody elektryczne made in China, których producenci korzystają z subsydiów rządowych niezgodnych nie tylko z przepisami unijnymi, ale też regułami Światowej Organizacji Handlu, do której Państwo Środka należy. Paradoksalnie na czele złożonego z pięciu państw członkowskich sprzeciwu wobec ceł były Niemcy, w których siedzibę ma Volkswagen. Liderem państw popierających cła na chińskie EV była Francja, z której wywodzi się jeden z filarów Stellantisa, czyli PSA.

Dlaczego Niemcy chcą umowy z Mercosur

Powody tych rozbieżności można sprowadzić tylko do kwestii ekonomicznych. Niemcy intensywnie handlują w Chinach, zarówno eksportując tam swoje towary, jak i prowadząc własną produkcję w chińskich fabrykach. Francuzi nie utrzymują zbyt rozwiniętych relacji handlowych z Państwem Środka – dość powiedzieć, że Pekin jako retorsję zastosował cła na sprowadzaną z Europy (głównie Francji) brandy.

Poza tym Stellantis przestawia się na produkcję wyłącznie elektryków. W ogromnej fabryce Stellantisa (kiedyś Fiata) w moich rodzinnych Tychach z taśmy zjeżdżają głównie elektryki.

Sprzeciw Niemiec wobec bardziej protekcjonistycznej polityki UE wydaje się mieć jednak głębsze podstawy. Niemcy po prostu nadal wierzą w skuteczność starego modelu wzrostu w Europie, czyli w promowaniu wolnego handlu. Problem w tym, że z tamtego modelu korzystali tylko czołowi eksporterzy, tacy jak właśnie Niemcy, Dania czy Holandia, za to mniej konkurencyjne państwa Europy Południowej musiały przejść przez niezwykle bolesny kryzys.

Obecnie Niemcy są też głównymi zwolennikami umowy handlowej z Mercosur, czyli grupą państw Ameryki Południowej – w tym jej największymi gospodarkami Argentyną i Brazylią. W tym wypadku znów po drugiej stronie sporu znajdują się między innymi Francja i Polska, w których dużą rolę odgrywa sektor produkcji rolno-spożywczej.

Umowa handlowa z Ameryką Południową wpuściłaby na unijny rynek znacznie tańszą produkcję z krajów Mercosur, co doprowadziłoby do wypchnięcia europejskich producentów lub obniżenia standardów zatrudnienia i produkcji w UE.

Ale Niemcy są także przeciwni europejskim fuzjom, chociaż sami wcześniej przejmowali flagowe przedsiębiorstwa z mniej zamożnych państw. Volkswagen przejął chociażby narodowe marki Hiszpanów (Seat) i Czechów (Škoda). Obecnie blokują przejęcie Commerzbanku przez włoski UniCredit. „Europa potrzebuje większych, silniejszych banków. […] Bez paneuropejskich czempionów wspólny blok nigdy nie zrealizuje swoich ambicji ani nie przezwycięży wyzwań rozwojowych” – stwierdził prezes UniCredit Andrea Orcel.

Powrót UE na fotel przynajmniej jednego z kilku globalnych liderów technologicznych i przemysłowych wymagać będzie pogłębienia integracji europejskiej. Tego zaś nie da się zrobić bez przymknięcia wspólnego rynku oraz jakiejś formy uwspólnotowienia finansów publicznych.

Przeciw temu wszystkiemu jest Berlin, który wyrasta na głównego hamulcowego integracji europejskiej, pod rękę z Węgrami i Słowacją, które nieprzypadkowo również głosowały przeciw cłom na chińskie EV. Rozeznanie w sytuacji i świadomość jej powagi wykazuje za to Paryż, który postuluje między innymi suwerenność strategiczną Europy i większy protekcjonizm.

Paradoksalnie więc przetrwanie i konsolidacja UE będzie zależeć od przełamania oporu Niemiec, którzy z niewiadomych względów uznawani są w Polsce – szczególnie po stronie liberalnej – za orędowników Zjednoczonej Europy. Nigdy nimi nie byli, a już na pewno nie teraz. Na szczęście sojusznikiem może być Paryż oraz przynajmniej część państw Europy Północnej i Południowej. Ewentualne i wciąż teoretyczne połączenie Pesy z Talgo byłoby znacznie bardziej proeuropejskie niż ostatnie postulaty idące z Berlina.

Wspieraj

Wspieraj

Wspieraj

Wspieraj  Wydawnictwo

Wydawnictwo

Zaloguj się

Zaloguj się